This article is published in Aviation Week & Space Technology and is free to read until Sep 12, 2024. If you want to read more articles from this publication, please click the link to subscribe.

Boeing Takes New Path To 777-9 Type Inspection Authorization

Three aircraft have joined the FAA certification flight testing that began July 12.

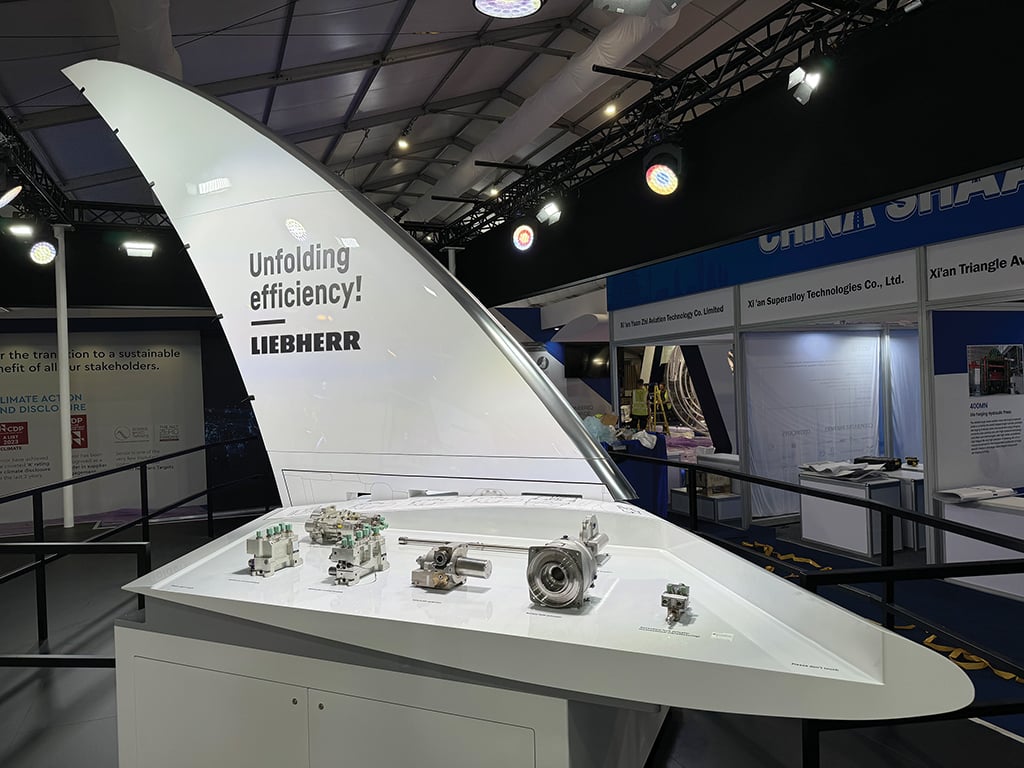

German supplier Liebherr’s massive Boeing 777X folding wingtip display, the largest tangible piece of the program at the Farnborough International Airshow in July, conveyed the airframer’s message about the 777-9: Every engineering and technical resource at the company’s disposal is in Seattle, focused on pushing the aircraft through certification.

As the clock ticks toward Boeing’s promised late-2025 target for clearing the long-delayed big twinjet for initial deliveries, the aircraft-maker is using the experience of the past four years to avoid last-minute surprises.

- Boeing enters final phase of 777-9 certification

- FAA scrutiny comes after new human factors validation steps

- First deliveries still set for late 2025

The first phase of 777-9 type inspection authorization (TIA), FAA-required testing for certification, began July 12 after a delay of almost three years. The tests are the last major milestone before anticipated FAA approval and long-awaited service entry. Boeing expects to make the first customer deliveries, once scheduled for 2020, late next year.

“We’ll continue to follow the lead of the FAA as we progress through the certification process and still expect first delivery in 2025,” Chief Financial Officer Brian West said on a July 31 earnings call.

With production-standard engines now being sent to Everett, Washington—most of the 30 or so 777-9s built have ballast hanging from their wings—the TIA pace and smoothness will dictate whether Boeing’s latest timeline holds up.

“We’ll take some time with the regulator and try to make sure that we go through lessons learned to get ready for TIA—and ensure we get all our homework done for the next phases,” says Mike Sinnett, vice president and general manager of product development at Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

The TIA is an internal document issued by the FAA that is customized to match a project’s requirements. Testing under the TIA can be done in steps or phases at the FAA’s discretion “to ensure basic airworthiness and that flight-test safety has been established before proceeding to the next phase,” agency guidance explains. Under the TIA, flight tests and other trials completed by an applicant to help establish an aircraft’s readiness for final FAA scrutiny are repeated by agency specialists or done under their supervision.

“We are working with the regulators to make sure that we’ve got a good process to work through the rest of TIA,” Sinnett says. “It’s changed so much—there’s no regulations that drive ‘here’s what TIA is’ and ‘here’s what you have to have.’ So it’s a collaborative approach to when we think we’re mature enough and ready enough to go through the different stages.”

Referencing programs such as the original 777-200, which obtained its TIA in July 1994 one month after first flight, and the 787, which received its initial phased TIA eight months after its first flight in December 2009, Sinnett notes how the process has become extended.

“Everybody’s been more careful, and there’s more scrutiny,” he says. “You can’t say it’s wrong, because you want to be so ready that you don’t have any surprises. And that’s one of the things that this scrutiny is forcing us to do: be really ready and confident when we start.”

The FAA rejected Boeing’s original TIA application in 2021, having found the aircraft and its systems to be insufficiently mature. Issues that extended the drive to the TIA included complying with new requirements to validate pilot-related human factors assumptions as well as satisfying regulator concerns around flight control redundancy and the 777-9’s common core computing and networking backbone systems.

Despite the twists and turns on the road to authorization for the start of tests for certification credit—which formally began July 12 with a flight by test aircraft WH003—there have been no specific changes made to the planned execution of the TIA process. “The scrutiny now helps us later,” Sinnett says. “You kind of have all your ducks in a row, and I believe it’ll make the back end flow more easily.”

A key takeaway for Boeing on its hard-earned TIA is applying the experience to preparations for follow-on derivatives.

“This is the next evolution of how the process will flow out, and what it’s doing is informing us for the 777-8F Freighter,” Sinnett says. “So as we’re building our plan for flight tests and certification for the -8F, we’re taking lessons learned out of the -9 right now.”

The test fleet’s latest flight-trial activity also reflects the early stages of TIA testing for certification credit. WH001 has flown regularly in the Puget Sound area, FlightAware data shows. Tests at the end of July focused on stability and control before shifting to aerodynamic loads surveying, sources with knowledge of the program tell Aviation Week. Those trials repeated work conducted four years ago following its first flight on Jan. 25, 2020.

WH002, also focusing on stability and control (see chart), conducted nearly 20 hr. of testing during three flights out of Kona, Hawaii, during the last week of July. It then returned to participate in the air show during Seattle’s annual Seafair summer festival on Aug. 4 before undertaking anti-ice testing on Aug. 7.

WH003 was in Colorado Springs July 29-31 for propulsion testing before moving to Toluca, Mexico. Both locations are well above sea level and provide ideal environments for required high-altitude performance tests. The aircraft then transferred to Kona for additional tests on Aug. 7.

The test fleet’s fourth member, WH004, performed some work early in Boeing’s testing but had not joined the TIA program as of Aug. 5. Boeing’s original test plan penciled in a fifth 777-9—designated WH006—but that aircraft has not yet been activated.

In the run-up to the TIA, the four 777-9 test aircraft had accumulated 3,500 hr. over 1,200 flights during a campaign that began soon after the January 2020 inaugural flight. Boeing’s TIA preparation also required completing two major firsts—one for the OEM and one for the industry.

The 777-9 is Boeing’s first aircraft that must meet all of the requirements in FAA’s Part 25.1302 regulation. Named “Installed Systems and Equipment for Use by the Flight Crew” and adopted in 2013, the complex rule expanded flight deck human factors considerations beyond pilot performance to aircraft design.

Aircraft manufacturers have long been required to consider how pilots would react to certain abnormal scenarios and develop both their designs and training to mitigate anticipated risks. Part 25.1302 builds on this by requiring certain levels of information—such as basic troubleshooting clues—in lieu of simple warning lights or sounds. The rule outlines parameters such as how the information should be presented—“avoid using many different colors to convey meaning on displays,” says a related FAA advisory circular—and how controls should respond. The goal is for designs to maximize the flight crew’s ability to troubleshoot problems while minimizing confusion.

Dovetailing with 25.1302 compliance are new requirements concerning human factors assumptions within system safety assessments (SSA). The steps are part of a 2020 law targeting improvements in how the FAA certifies aircraft following the two 737-8 accidents, one in 2018 and the other in 2019.

Among the myriad issues flagged: Some of Boeing’s assumptions about how pilots would react in certain scenarios proved incorrect. Since much of the 737 MAX’s certification work was delegated to Boeing employees designated to act on behalf of the FAA under the agency’s Organization Designation Authorization program, agency experts did not double-check every SSA assumption.

The 2020 law requires the FAA to review and sign off on all underlying human factors assumptions meant to help a critical system show compliance with a rule. Approval must come before related work can continue. This makes the validations a critical new gate in the certification process.

One element of Boeing’s approved validation process involves extensive use of line pilots. More than 200 pilots participated in trials to help Boeing develop and test various assumptions.

Line pilots have long participated in the FAA Flight Standardization Board flight crew training evaluation phase—one of the last steps in any large-transport certification program. The FAA formally expanded the process to require more pilots of various experience levels based on lessons learned from the 737-8 accidents (AW&ST Jan. 25-Feb. 7, 2021, p. 45).

But the human factors validation requirements are so new and complex that the FAA has not issued a rule or guidance on how to comply. Boeing and the agency collaborated on developing a process that includes an issue paper, or project-specific set of requirements, for the 777-9.

The FAA and Boeing also applied lessons learned from work on the manufacturer’s two other certification programs, the 737-7 and 737-10, that are farther along than the 777-9 and were required to comply with the 2020 law.

Part of the plan calls for incorporating feedback from active line pilots. The work, done in both static engineering and full flight-training simulators, puts flight crews through some 1,000 Boeing-developed scenarios, 777 Chief Pilot Ted Grady told Aviation Week during a recent visit to Boeing’s 777 production facility in Everett.

“Our test plan includes a diverse group of pilots of varying experience levels from around the globe,” Grady said. “We’ll run them through, see how they perform, get their feedback. We collect all that data and present it to the FAA.”

Standardized documents, including a crew operations validation worksheet and crew response assumption identification template, helped ensure data collection consistency. The documents were developed with the FAA’s help, according to correspondence between the agency and the NTSB, which issued a related recommendation in 2019.

The process not only helped Boeing validate safety assessment-related assumptions but also provided another layer of scrutiny of basic human factors issues.

“It might be the syntax on some [engine-indicating and crew-alerting system] alert,” Grady said. “We changed the wording because it’s familiar to us as engineers, but the line pilot [said]: ‘What does that word mean?’”

The reviews covered every pilot-related aspect of the 777. New functionalities, such as the folding wings that make the 777X family compatible with more airports and the touch screens on the flight deck, received special emphasis.

“We make some assumptions based on our experience, based on our background,” says Heather Ross, 777 deputy chief pilot and a former line pilot with extensive experience on multiple Boeing aircraft types. “We have an idea, and then we go out and present [to] pilots that don’t have specific training on this model. They go out and fly the simulator. Sometimes we’re surprised—[we] didn’t expect that. OK, another great data point. It’s all part of the learning process. We can make our products better because of it.”

Boeing’s market-driven goal for the 777X family is to provide a more efficient replacement for large widebodies. The manufacturer aims for the aircraft to handle like the original 777 while incorporating new technology, notably a redesigned flight deck introduced in the 787.

“The goal was to make the 787 fly just like the [original] 777,” Ross says. “The 777 is loved by our customers and pilots. Now we’ve got to come full circle.

“We were pretty successful at keeping those great handling qualities that we loved in the 777 and bringing them over to the 787,” Ross adds. “Now we’re bringing that new technology and updated flight controls back to the 777-9.”